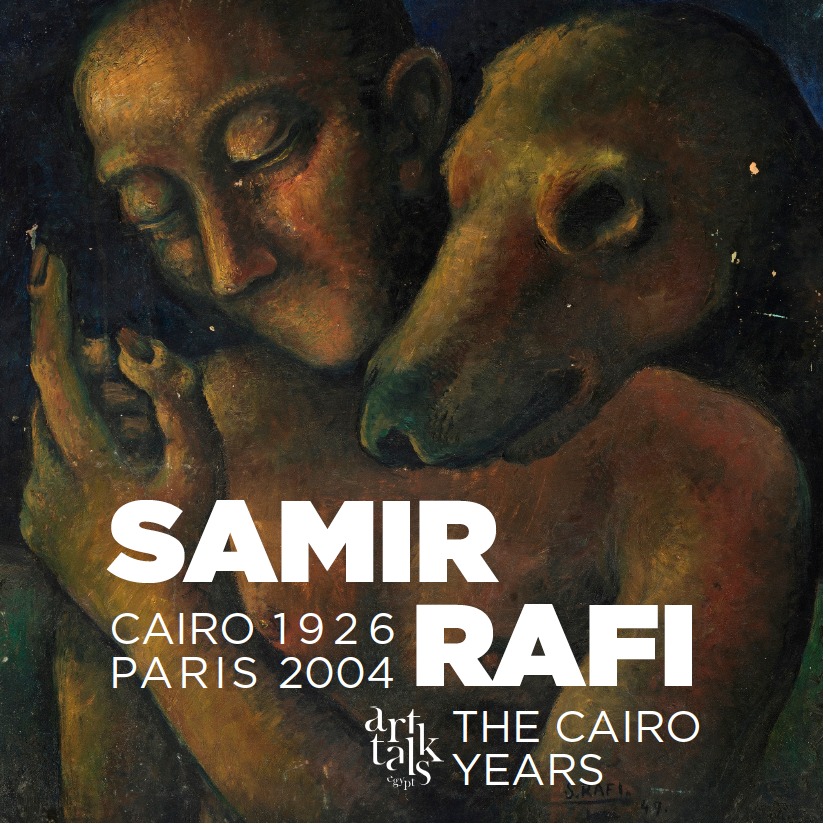

Samir Rafi’s Cairo Years invites a deeper examination into the “Rafi’sm” school of art, thereby recognizing Rafi as the pioneer he truly was. As we take a closer look at the works produced between 1941 and 1954 presented in this exhibition for the first time in over six decades, we come to understand how Rafi’s pioneering work advanced, if not masterminded Egyptian Surrealism, and influenced various movements and artists thereafter, making Rafi an essential part of the re-envisioning of Arab art history.

Intriguing, Samir Rafi was a highly individual artist, who seems to have never admitted that the grass was not greener after all on the other side. Driven by his blind ambitions to impact the world, he sacrificed homeland, wife, children, friends, and colleagues, when he decided to migrate and spent the last decades of his life, in seclusion in Paris. Only Sami (1931-2019), his younger brother and the architect behind the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, remained his lifetime pen friend and confidant. Distant from the region for over half a century, Rafi paid a hefty price as he did not receive the attention bestowed upon his more famous “brethren” of the Contemporary Art Group, Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar and Hamed Nada in particular as they continue to be the hottest subjects for museum exhibits and auction sales. By the time of his death, Rafi belonged neither in Egypt nor in France, and his ability (or rather inability) to overcome obstacles became the subject of his work which explains the more somber, enigmatic, highly sexual and darker side. Neither celebrated in the Arab world, nor recognized as he had expected in Europe, his legacy began to be revived when all his belongings, scattered in his two-bed room apartment in Paris, were returned to Cairo by the Ministry of Culture following his death in 2004. Only then did Rafi begin to “taste” the appreciation he truly deserves in his homeland, as well as in the so-coveted Western world, and become the subject of many controversies. His legacy, persona and oeuvre are now being scrutinized. Many stories are told, triggered by family feud, unpublished letters that are being discovered in which he attacked key players and revealed a different history to the events, as well as press articles, to which he responded, or others left unanswered since they were published after his death.

Lying somewhere between a tale of hope and the tragedy of hope, Samir Rafi’s life and work were also the subject of three Arabic-language books. The title of Samir Gharieb’s book is a resonating description. Titled The Impossible Migration: From Darb al-Labbana to Paris (Cairo: 1999), Gharieb’s book is primarily based on letters by Samir Rafi written between 1986-88 to his brother Sami, and on interviews the author held with Rafi in Paris in 1997. Likewise, the two books by Abdelrazek Okasha, published in 2007 and 2012, are based on interviews the author held with Samir Rafi in Paris. Interviewed at a time when Rafi was past his seventies, some of the accounts certainly lack in objectivity and demonstrate a rather bitter persona who views himself as a constant victim, and judges the other artists as imitators to his unique style. This is further demonstrated in handwritten letters dated August to November 2000 acquired by ArtTalks from the archive of the late art critic Mokhtar al-Attar. By then, many of the key protagonists, who participated in or shaped Rafi’s life one way or another, had passed away and could no longer respond to the accusations or confirm the veracity of Rafi’s account of events. This forces us to take the stories published with a grain of salt since many are one-sided. To add to the complexity, Rafi’s exceptionally prolific production, divided in two periods (Egypt until 1954 and post-Egypt), is scattered around the world and exceeds thousands of paintings using different media, (lost) objects and sculptures, drawings, collage, sketchbooks and tapestries. Despite the dispersion of his oeuvre and the immense confusion in historical facts, this exhibition is both a tribute to Rafi’s Cairo Years, and an attempt to divulge some truth. This, until we complete the first English-language monograph dedicated to the artist as we aim to call for a deeper examination into folk surrealism to seal Rafi into the historical art cannon. In one of the letters Rafi addressed to al-Attar, Rafi agreed to publish his biography as he wanted ‘to correct history’ and remedy the historical oblivion of his legacy. In the letter, he admitted that ‘the whole responsibility falls upon [himself], as [he] had chosen silence.’ Samir Rafi’s Cairo Years aims to break that silence.