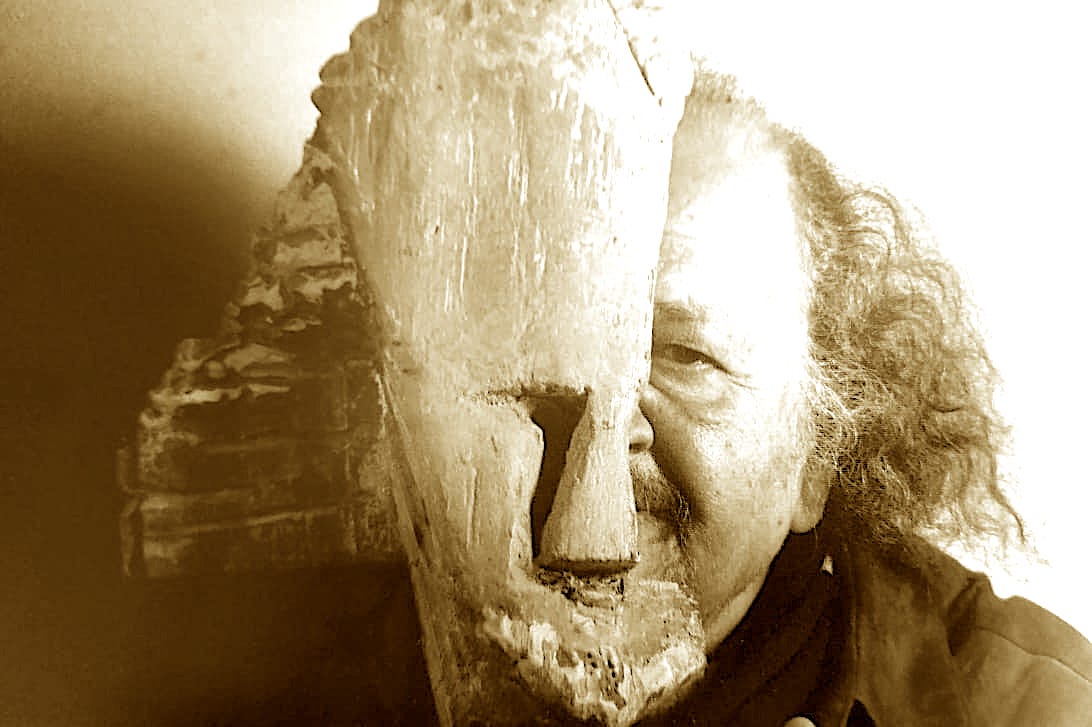

George Bahgory is widely known as a cartoonist, but he is much more. A prolific multimedia artist, Bahgory is a painter, sculptor, poet, and writer. His media is as diverse: Sculptures, paintings, sketches, lithographs, tapestry, collage, drawings, using oil, watercolor, coffee, china ink, pen, and pencil; on canvas, paper, filter coffee, clay, bronze, stone. Bahgory was dubbed “The Picasso of Egypt,” “Picasso of the Arabs,” “The Painter Between Two Riverbanks,” “The Master,” “A Unique Phenomenon,” “The Rebel,” and “The Beethoven of Fine Arts.” As someone who claims to have been born twice, the first time in his native Egypt on 13 December 1932 and the second time [une deuxième naissance] in his adoptive France on 25 August 1969, George Bahgory is bold, frank, and never hesitates to fight for free speech. He was in trouble with the government of former presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anouar el-Sadat. He appreciates all women, repeated senior year in high school three times (1949, 1950, 1951), prefers to draw upside down, and is still active to this day, painting, touring exhibitions, socializing at the young age of 90.

I go through the thousands of pages I am blessed to have and discover many facets unknown to the public. For example, Bahgory has over 1,000 sketchbooks or “carnets de voyage,” as he likes to call them, stored in his atelier. In there, you can meet his humble family: his mother Elisse, his father, Abdel Messih, his older brother Johnny, his sister Evelyne, his wife Nitokriss, and the rest of his private tribe from cousins and nieces to next-door neighbors. Another example is that his name Bahgory derives from “Bahgora,” the village where he was born next to Luxor in Upper Egypt. He also writes his names in different ways. George. Georges. Bahgory. Bahgoury. al-Bahgory. Or is it us who do? It doesn’t matter. George Bahgory is unique.

One of the sketchbooks titled “The Forbidden Drawings” is a rich and valuable documentary where Bahgory narrates his life as a student in the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cairo (1951-55). He drew his colleagues, professors, and future bosses, like his mentor Hussein Bicar, modernist painters Ahmed Sabry, Abdel Hady el-Gazzar, el-Seginy, and journalist Ihsan Abdel Quddous. The latter eventually hired the then twenty-two-year-old Bahgory and launched his two-decade career as a caricaturist of satire responsible for the weekly cover of Rose al-Yusuf magazine. At the time, Bahgory’s father, Abdel Messih, urged George “to stop scribbling, forget about art, and to study medicine instead” [Balash Shaghbata! Sibak min al-fann, wa idriss al-Teb!] But Bahgory didn’t bulge, poised to make a pioneering career in satirizing Egyptian politicians, ridiculing government decisions, narrating daily life and ordinary people’s hardships for the only reason to tell it like it is. According to Bahgory, it was a period of press vibrancy, during which Egyptians appreciated an ironic sense of humor and supported fierce free speech. Caricature was a flourishing art form thanks to the renowned “creative block” consisting of Salah Jahin, Ragai’e, El-Selmi, Bahgat, Hegazi, el-Labbad, amongst others. But soon enough, censorship had its toll on the “industry,” and Bahgory’s drawings began to attract if not bother Egypt’s leaders’ attention, unhappy to be mocked on the cover of the most widely distributed magazines in the Arab world. Nasser was poked by his immense nose and authoritarian persona, while Sadat was cornered when he envisioned the Camp David Accord. In 1967, the year of the Hazimah, artists were threatened, and the “fall of caricature” art [Soukout al-Karikatiruiyya] in Egypt led many to choose exile over compromising on their ideals and values. Once Bahgory felt the artist’s right to free brush was jeopardized, he decided to leave for France and began a new and, at first, difficult life in Paris.

Painters are usually categorized. They also have stages or periods. George somehow escapes because he practices and produces works that fluidly move from one category or period back to another. There is a sort of épuisement du thème. In other words, Bahgory expends themes, repeating the same subject over and over, each time adding a new element or showing a different perspective while using new color palettes or media. It reminds me of what he said: “I start from the end so that I reach the beginning,” establishing a signature style that no two people would miss. Bahgory is instantly recognizable, even to the untrained eye. This probably explains why the Egyptian State awarded him the Prix d’État d’Excellence dans les arts in 2006. There is no key in George Bahgory’s work. Only a sense of rush. He always seems to be in a hurry, as though he is trying to capture the moment, live that instant, and not miss the smile, the crowd, the music, the people, his people, our people.

How beautiful life is without a key!